Posts by hdcoadmin

Kentucky budget cuts deprive poorer youth

“These days, Terry, (Mike) Newman and tens of thousands of other low-income Kentuckians feel under attack. Subsidies for child care and kinship care, the two state programs most central to their lives, which allow them to parent and prevent their fragile work routines from collapsing, were all but eliminated from this year’s budget. Earlier this week, families rallied in Frankfort,…

Read MoreLaw Enforcement Can Sell Confiscated Guns

“For decades, weapons confiscated by police in Texas were supposed to be repurposed for law enforcement use — or else destroyed. Starting next month, Texans will be able to purchase some of them instead,” according to a Texas Tribune report.

Read MoreMinneapolis mayor’s race lags in disclosing campaign contributions

The Minneapolis Star Tribune reports: “If candidates for mayor of Minneapolis were running in Boston, they would file a report online of their campaign contributions every two weeks for six months before the election. If they were running in Seattle? Once a week. And in a range of other cities with a mayoral election this fall, they…

Read MoreNSA Officers Spy on Love Interests

The Wall Street Journal reports: “National Security Agency officers on several occasions have channeled their agency’s enormous eavesdropping power to spy on love interests, U.S. officials said. The practice isn’t frequent — one official estimated a handful of cases in the last decade — but it’s common enough to garner its own spycraft label: LOVEINT.”

Read MoreAfter West disaster, News study finds U.S. chemical safety data about 90 percent wrong

“Even the best national data on chemical accidents is wrong nine times out of 10. A Dallas Morning News analysis of more than 750,000 federal records found pervasive inaccuracies and holes in data on chemical accidents, such as the one in West that killed 15 people and injured more than 300.”

Read MoreCIA Files Prove America Helped Saddam As He Gassed Iran

“The U.S. government may be considering military action in response to chemical strikes near Damascus. But a generation ago, America’s military and intelligence communities knew about and did nothing to stop a series of nerve gas attacks far more devastating than anything Syria has seen, Foreign Policy has learned.”

Read MoreBack Home: The enduring battles facing post-9/11 veterans

“In the 12 years since American troops first deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq, more than 2.6 million veterans have returned home to a country largely unprepared to meet their needs. The government that sent them to war has failed on many levels to fulfill its obligations to these veterans as demanded by Congress and promised…

Read MoreExtra Extra Monday: Chemical safety data, post-9/11 veterans, NSA love interests

Back Home: The Enduring Battles Facing Post-9/11 Veterans | News21“In the 12 years since American troops first deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq, more than 2.6 million veterans have returned home to a country largely unprepared to meet their needs. The government that sent them to war has failed on many levels to fulfill its obligations…

Read MoreThousands of physicians still practicing despite misconduct

The nation’s state medical boards continue to allow thousands of physicians to keep practicing medicine after findings of serious misconduct that puts patients at risk, a USA TODAY investigation shows. Many of the doctors have been barred by hospitals or other medical facilities; hundreds have paid millions of dollars to resolve malpractice claims. Yet their…

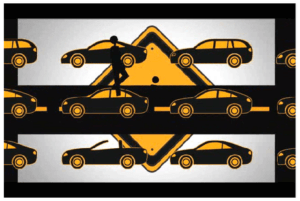

Read MoreAssessing and mapping dangerous intersections, traffic fatalities in your community

A still image from the Orlando Sentinel’s Blood in the Streets animated video. By Scott Powers and Arelis Hernandez, the Orlando Sentinel This past winter, after an Orlando Sentinel editor almost ran down a pedestrian for the umpteenth time – a moment which occurred about the same time that our breaking-news desk had to write…

Read More Don't wait until the last minute! The

Don't wait until the last minute! The