Posts by hdcoadmin

Victims’ Dilemma: 911 Calls Can Bring Eviction

“Aiming to save neighborhoods from blight and to ease burdens on the police, municipalities have adopted ordinances requiring landlords to weed out disruptive tenants,” The New York Times reports.

Read MoreLocked in Terror

The Fresno Bee reports: “The Fresno County Jail has been a place of terror and despair for mentally ill inmates who spiral deeper into madness because jail officials withhold their medication. About one in six jail inmates is sick enough to need antipsychotic drugs to control schizophrenia, bipolar disorders and other psychiatric conditions, but many…

Read MoreCostly perk forces DWP to shell out extra if it gives work to outside contractors

The Los Angeles Times reports: “It’s no secret Los Angeles Department of Water and Power employees are paid well. But a little-known clause in their union contract ensures they can work extra hours and collect even higher wages when private contractors are hired to help them get the job done.”

Read MoreNew York Promised Help for Mentally Ill Inmates — But Still Sticks Many in Solitary

“In New York, inmates diagnosed with ‘serious’ disorders should be protected from solitary confinement. But since that policy began, the number of inmates diagnosed with such disorders has dropped,” according to a ProPublica report.

Read MoreTaken

A New Yorker article states: “The basic principle behind asset forfeiture is appealing. It enables authorities to confiscate cash or property obtained through illicit means, and, in many states, funnel the proceeds directly into the fight against crime. But the system has also given rise to corruption and violations of civil liberties. Over the past…

Read MoreExtra Extra Monday: Mentally ill inmates, sex predators unleashed, civil liberties violations

Sex Predators Unleashed | Sun-Sentinel“Another child is dead. This time, a brown-haired, brown-eyed girl, a year younger than Jimmy Ryce. A 1999 law passed after Jimmy was raped and murdered at age 9 is meant to protect Floridians from sex offenders by keeping the most dangerous locked up after they finish their prison sentences. But…

Read MoreEven Small Amounts of Precipitation Dump Raw Sewage into Potomac River

Don’t believe the signs city officials have posted at the four outfall spots that dump raw sewage into the Potomac River. The truth is much worse.

Read MoreDocuments show NSA broke privacy rules thousands of times per year

The National Security Agency has broken privacy rules or overstepped its legal authority thousands of times each year since Congress granted the agency broad new powers in 2008, according to a report from The Washington Post. Based on an internal audi and other top-secret documents provided by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden, The Washington Post…

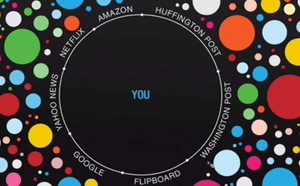

Read MoreNew webinar: Search strategies, sites and databases for investigative reporting

Watch now: Search strategies, sites and databases for investigative reporting Google’s not the only search game in town. Learn about search sites that provide different pools of information and unique features. Discover resources to help with people finding, fact-checking and social search in the surface and the deep Web. Barbara Gray, Distinguished Lecturer & Interim…

Read MoreInspection, enforcement of Pennsylvania amusement parks fall short

Pennsylvania has more amusement park rides than any other state, and its governer has stated its rides are unmatched in safety because of the state’s rigorous inspection program. But an investigation by PublicSource shows that the state agency that oversees amusement parks does not track the safety inspection reports that parks are required to file…

Read More Don't wait until the last minute! The

Don't wait until the last minute! The