If you fill out the "Forgot Password" form but don't get an email to reset your password within 5-10 minutes, please email logistics@ire.org for assistance.

On Aug. 23, 1999, just after 8 a.m., regional supervisors for the Arkansas Health Department started getting phone calls from county health officials. Not exactly the most breaking news of the day, but what set those calls apart was this: All the callers were saying the same thing. People had showed up at their offices asking for records. What should they do about it? As more and more calls were fielded, the officials began to realize that something was different — and that a coordinated effort was clearly being made.

“My best guess is that we were tested this morning by some group outside the agency to see how we respond to FOI-type requests,” Jim House, a regional supervisor over several county health units, wrote in a department email that afternoon.

One might be forgiven for thinking that conspiracy was afoot. However, the truth was revealed several weeks later when newspapers across the state published a special section under the heading “The FOIArkansas Project.” In a series of articles, the editors from six Arkansas news organizations outlined how, on that day in August, they’d sent 75 people to all of Arkansas’ 75 counties to test public officials’ compliance with freedom-of-information laws.

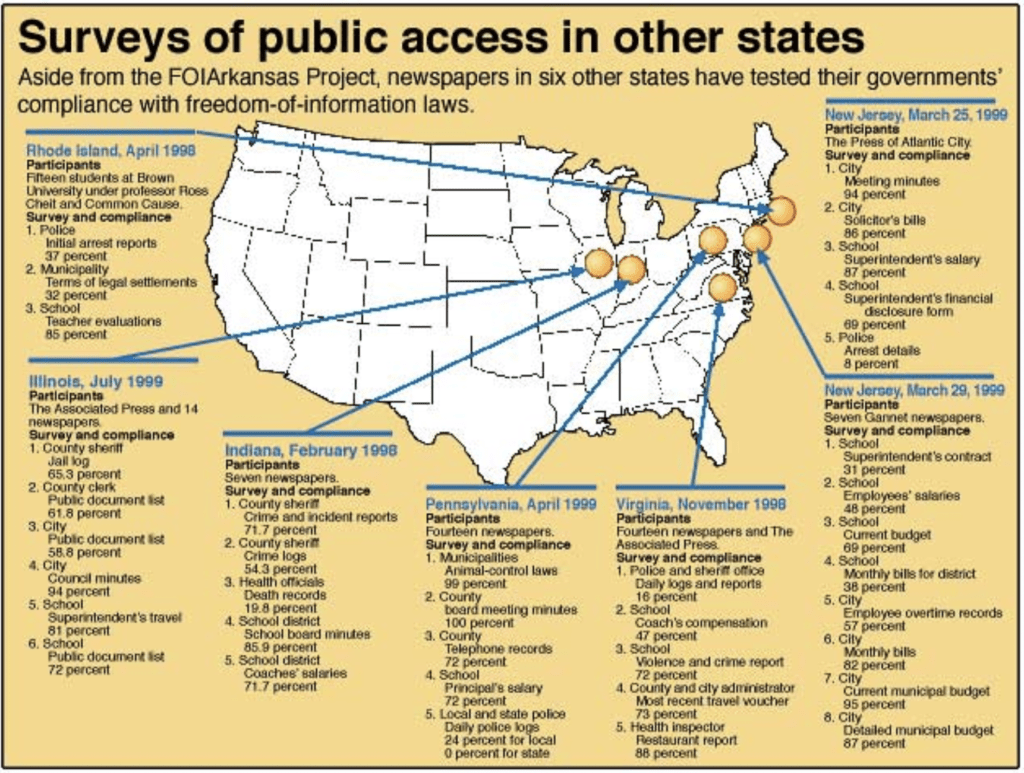

In some respects, their work in Arkansas wasn’t altogether novel. On one page of the special section, a map highlighted similar FOI surveys that had been conducted in other states: Beginning with Indiana in February 1998 and continuing through Illinois in July 1999, each entry noted the participants and the rates of compliance that the survey had found. Even within individual states, these ranged from the nearly perfect (New Jersey city meeting minutes with 94%) to the less-than-perfect (New Jersey arrest details with 8%).

The truth, however, is that the first steps had been taken nearly seven years before the Arkansas audit. According to the National Freedom of Information Coalition (NFOIC), the first audit “we’ve a record of was conducted by the Oakland Tribune and the First Amendment Project in 1992 to test how well 30 Bay Area agencies were complying with the California Public Records Act.”

A November 1992 article in the Oakland Tribune explained that the effort, known as the California Sunshine Survey, had been prompted by a desire to see how well state agencies were complying with the California Public Records Act (CPRA).

“[CPRA] was meant to give the public the right to see government documents, a right that previously existed in name only,” the newspaper noted. “But civil liberties activists and many journalists say the fight for the right to know is still being waged.”

Passed in 1968, CPRA was among the many state laws that had been passed in the wake of the federal Freedom of Information Act, which had been signed into law in 1967. (It wasn’t until 1974, in the wake of the Watergate scandal, however, that the federal act was endowed with its current teeth.) Nearly 25 years after CPRA’s passage, however, there were doubts that government agencies were living up to the law’s requirements — something which researchers soon confirmed.

“It felt strategic,” said Eric Newton, then-managing editor of the Oakland Tribune. “We were going to see if these guys were following their own laws.”

According to the Oakland Tribune article, the survey — which asked 30 Bay Area city, county and regional governments and agencies to detail how they responded to records requests between August 1991 and August 1992 — found that a significant percentage of those surveyed failed to meet the law’s requirements:

“Ten of the government agencies failed to comply with the law's 10-day deadline for answering requests.”

“Only half of the agencies have a written document that employees can use for guidance when confronted with a request under the records act.”

“Ten of the agencies charged more for documents than media lawyers considered reasonable.”

A few years later, in 1995, the Associated Press conducted an audit in Arizona. In 1997, a group of university students in Rhode Island conducted an audit of their own on 39 cities and towns in the state. In 1998, according to the NFOIC, the aforementioned Indiana audit “set the model for state audits.” A flurry of audits across the country then followed — more than 60 between 1998 and 2004 — most of them finding that, in the absence of watchdogs breathing down government agency necks, compliance often tended to suffer.

Charles Davis, then the SPJ FOI Committee Co-Chair, began hearing from organizations across the country interested in conducting audits of their own, (“I don't know how in the world this happened, but somehow I became sort of recognized as the person to call if you were about to do an audit,” he said). To help expedite those processes, he helped compile a 39-page “FOI Audit Toolkit,” which included a guide to developing audit questionnaires, training auditors, along with sample forms that had been used by five different statewide audits.

Although there was some nuance to determining exactly how to proceed with an audit — for example, it was important to ask for records that would be easily accessible and not require a significant amount of legal wrangling — at heart, the idea of an audit was simple.

“[It] sounds simple, because it is pretty dang simple: You ask for records and you find out what the response is,” Davis said. “I think it's a great test of the civic health of a community — maybe the best test — because if you go out and get some pretty foundational documents about your community, it's a community that's fairly transparent and running pretty well. And if you can’t — that worries me.”

What those audits allowed the public to realize is that journalists hadn’t just been making frivolous complaints about one-off interactions with recalcitrant record keepers. This was hard data. And as Davis noted in the toolkit, that data was capable of having real-world effects: In New Jersey, for example, reporters fanned out across 14 of the state’s 21 counties in 1999, and found that half of all legitimate public records requests were denied. In 2002, New Jersey enacted a newly revised sunshine law.

“The audit was a huge part of the equation,” Paul D’Ambrosio, investigations editor of the Asbury Park Press, was quoted as saying in the toolkit. “It played a major role in creating the environment for legislative change.”

By all accounts, the era was a high-water mark for open records advocacy — something driven even further by then-current events. (“After 9/11, and particularly when we entered our war into Iraq, that created a lot of backlash to the secrecy,” said David Cuillier, director of the Brechner Freedom of Information Project at the University of Florida. “Then we figured out, Hey, we've been lied to.”) State FOI groups were active, and multiplying, across the country. Sunshine Sunday got its start in Florida in March 2002, and went national three years later with Sunshine Week. Davis, who was then the executive director of the National Freedom of Information Coalition, recalls up to four states a year being added to the coalition’s swelling membership ranks.

“Media companies had budgets, they had lawyers — hell, they had employees,” Davis said.

However, as legacy media operations were largely left behind during the mid-aughts’ digital transformation, budgets were cinched tighter and audits became largely a novelty, rather than a necessity. There were some additional audit efforts to move the needle on the federal side of the fence — notably, the Knight Open Government Surveys, the last of which took place in 2011 — but ultimately, according to Cuillier’s research, we’ve been a steadily rising move toward government secrecy. (In one instance, Cuillier found that, according to the federal government’s own data, the percentage of petitioners who received all of their requested information dropped from 38% in 2010 to 12% in 2024. In the same period, he found that the number of backlogged requests had risen from 69,526 to 267,056.)

“Government secrecy is just continuing to increase, according to our data, it just continues to increase every year, little by little,” he said. “We haven't had any major events really that have pushed people to take this seriously again — although I think we're starting to see some of that under our current presidential administration. So, I anticipate we'll see more interest in pushing for government transparency as the current federal government becomes way more secret than it ever has been.”

Still, as both Cuillier and Davis note, there are still roads ahead, especially for collaborations that extend outside newsrooms.

“I would love to see journalists turn to universities and say, ‘Hey, about you give me a class and we'll do an audit,’ because all an audit really needs is muscle,” Davis said. “There's no magic here. It's just sweat equity.”

These days, visitors to foiarkansas.com won’t find much about open records or FOI advocacy. Since at least July 2016, the website, which once acted as a repository for the early FOIArkansas efforts working to bolster the state’s open records laws, now offers, in Spanish, a guide to cryptocurrency. “Foiar Kansas,” reads the text at the top of the page.

And yet, the legacy of those early advocates haven’t been lost entirely. A digital backup of FOIArkansas remains available online thanks to the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. But that legacy has also found new life outside the digital sphere.

On Nov. 15, 2024, 16 pairs of students from the University of Central Arkansas spread across Faulkner County. Although the scale was considerably less ambitious than the 1999 audit that had inspired it. (They had also gotten inspiration from a similar project done at Arkansas State University in 2009), the aim was virtually the same: The students approached a range of public agencies — including police departments, the sheriff’s office, the school district and others — and documented their experience in requesting public records.

“We’re testing to make sure that the people who are assigned to follow the law know what the law is that they follow,” says David Keith, a UCA professor who advised on the project. “The thing about the FOIA is it is a law in this state, just like any other law.”

As one of the participating students, Torrie Herrington, noted in an article she wrote about the audit, some students did face pushback from officials, but on the whole the agencies they queried were largely cooperative.

Rob Moritz, a UCA journalism lecturer and FOIA Task Force Chair (whose second term comes to a close on Aug. 1), mentioned that the Arkansas SPJ chapter had considered coordinating another statewide audit, though he was quick to note that the challenges would go beyond logistics.

“The Maumelle Monitor no longer exists. The North Little Rock Times no longer exists. The Sherwood Voice no longer exists. The Cabot paper no longer exists. The Lonoke paper no longer exists,” Moritz said, noting that Gatehouse Media’s acquisition of Stephens Media and subsequent shuttering had led to many papers’ closure. “There’s nobody there, and so [an audit] would be very difficult.”

In some respects, Arkansas’s Freedom of Information Act — which was signed into law on Valentine’s Day 1967, just a few months before the federal law took effect in July — has offered a stand-up model for open record laws, unlike many other states where once robust records laws have suffered thousand-cut deaths. For the past decade, however, as Arkansas lawmakers have made repeated efforts to slowly chip away at the law’s efficacy, that transparency has increasingly come under threat. It’s true that many of those efforts have flopped, even resulting in unlikely alliances of oil-and-water political opponents. But only a few have to succeed for there to be real-world ramifications.

Of course, this is hardly limited to Arkansas. And as Cuillier notes, although there are challenges, the stakes have never been higher — and the need to challenge government secrecy is more than just about getting jail records and school board minutes.

“It's frog-in-the-kettle — we've gotten used to it, little by little, just inching more toward secrecy. Some people don't notice it. And, you know, we'll reach a time, the tipping point where it's all gone,” he said. “I hate to sound so negative, but that's what we have to avoid — and so it's all hands on deck if we want to save our government, our democracy, our republic.”

Jordan P. Hickey is a Northwest Arkansas-based freelance journalist whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, VQR, Southern Foodways Alliance, among others. In 2025, he was a finalist for the James Beard Awards in Profile Writing, and is currently a Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future Food Systems and Public Health Fellow.

Looks like you haven't made a choice yet.