If you fill out the "Forgot Password" form but don't get an email to reset your password within 5-10 minutes, please email logistics@ire.org for assistance.

You might think you have to kill someone to be charged with murder. But at least in Illinois, you’d be wrong.

In an investigation for the Chicago Reader, independent journalists Alison Flowers and Sarah Macaraeg spent several months looking into a controversial law called the “felony murder rule,” which says that if a person commits a felony, he or she can begin a chain of events that results in another person’s death. Even if the felon isn’t the killer, he or she can still go to prison for murder.

The use and impact of the law have raised questions. Flowers and Macaraeg found ten cases in Chicago’s Cook County in which killings by the police resulted in felony murder charges for someone else involved in the case. What’s more, legal experts told the reporters that felony murder charges are often an indicator of wrongdoing by police.

“The chief injustice that we’re trying to point out is that this can actually become a red flag for police misconduct,” Flowers said. “I don’t think it’s any coincidence that the people we found who had these real stories to tell are people of color.”

Felony murder laws exist in most states, many contain separate “protected person” rules that prevent an arrestee from being charged with a co-arrestee’s death, or rules that require that the killer be a participant in the felony. That’s not the case in Illinois.

Discovering the law

"The fact that we’re able to do this type of work as independent journalists … dismantles the lone wolf caricature of investigative reporting. The stronger your team, the better your work."

– Sarah Macaraeg

Flowers and Macaraeg have a long history of covering the criminal justice system. As longtime friends and collaborators, they meet regularly to talk about what they’re working on.

In January, Flowers was covering the police shooting of Cedrick Chatman for VICE and she was surprised to learn that two men who were with Chatman when he was killed faced murder charges for his death.

In 2015, Macaraeg had a similar finding. She was working on a story about the Chicago police department recategorizing fatal police shootings to make the numbers appear lower than they actually were. She noticed one case in which police killed a man who had just robbed a gyro shop. His co-arrestee, who wasn’t there when the man was shot, was charged with his murder.

“Even in the report of the independent police review authority, which justified the shooting, it was just so clear there was a story there,” Macaraeg said. “It was very sad.

A couple months later, Macaraeg was working on a story for The Guardian about coerced confessions by Chicago police. The felony murder rule came up again: A local police commander had killed four different people, and in the last case a civilian was charged with the murder instead of the officer.

Both reporters knew that this law was something they wanted to cover in-depth. When they met up in February, they realized they were both working on the same issue.

“It really was an organic process of meeting up for coffee or Manhattans to talk about what we were working on and trends we were hearing about,” Flowers said.

They started laying the groundwork for an investigation, writing letters to prisoners and filing FOIA requests about their cases. A couple months later, they committed to diving into the investigation together.

“The fact that we’re able to do this type of work as independent journalists… dismantles the lone wolf caricature of investigative reporting,” Macaraeg said. “The stronger your team, the better your work.”

Shoe-leather investigating

Flowers and Macaraeg began with the felony murder cases they already knew about.

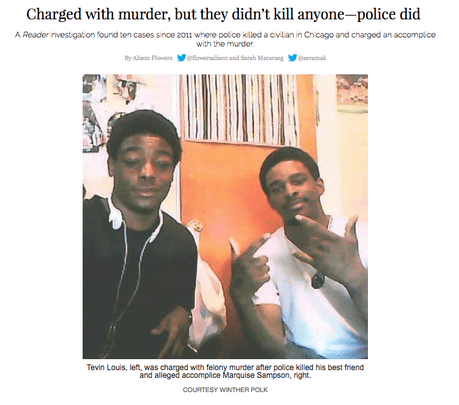

The gyro shop robbery case that Macaraeg noticed became the investigation’s opener, telling the story of Tevin Louis and his best friend Marquise Sampson.

Elyse Blennerhassett, a multimedia producer and friend of Flowers’, told her about the case of Tristan Scaggs.

In 2006, Scaggs and two friends were driving around in a stolen Pontiac Grand Prix. Police stopped and surrounded them, firing more than 60 shots into the car. Scaggs was shot and both of his friends were killed. Scaggs was charged with his friends’ murders, and he is now serving a 38-year sentence.

After Blennerhassett put Flowers in touch with Scaggs, she found that he was being represented on a post-conviction petition by a lawyer she had worked with during a previous job at the Medill Innocence Project. She helped Flowers set up phone calls with Scaggs, where she could hear his story.

Identifying people affected by the law required patience; it took time for prisoners to respond to letters or for court hearings to take place.

“For some people who were being adjudicated, I went and sat in court all day just to see them come up in the status hearing,” Macaraeg said. “Which meant that I then met their family members and their lawyer. … There were some relationships that just really took off.”

Macaraeg said her reporting was an ongoing cycle: She would get in touch with prisoners and then file FOIA requests for documents related to their cases.

A breakthrough moment

Charges under the felony murder rule aren’t always easily identifiable, so finding aggregate data on trends in the law proved to be challenging at first.

“It’s not as if there’s any manual anywhere that helps you understand how it is that people go to prison and under what charges,” Macaraeg said. “The puzzle piece was how do you isolate things down to felony murder. We did research, but it wasn’t immediately apparent.”

Flowers reached out to her former colleagues at the Innocence Project to see if they might have some data. In the meantime, they looked up individual cases in the Illinois Department of Corrections offender search tool.

“I was looking for their addresses to write them. But if you’re an investigative journalist, you read everything,” Macaraeg said.

She noticed that the people she was looking up were often charged with “Murder/Other forcible felony.” Other murder cases were coming up as “Murder/Intent to kill.” They decided to explore the differences between those charges, and submitted a FOIA request for information related to the cases deemed “other forcible felonies.”

She noticed that the people she was looking up were often charged with “Murder/Other forcible felony.” Other murder cases were coming up as “Murder/Intent to kill.” They decided to explore the differences between those charges, and submitted a FOIA request for information related to the cases deemed “other forcible felonies.”

However, the data that came back from Cook County wasn’t perfect. They were hoping to get a list of everyone charged under the felony murder rule. What they got only showed felony murder charges that later resulted in convictions.

It was important for them to show how often charges were being brought — not just how many people were sent to prison on them — because even if the charges are later dropped, they can have a profound intimidation effect on defendants, causing them to accept other charges they’d otherwise fight. They used the data to provide a snapshot of how frequently felony murder charges were happening, and ended up telling Tevin Louis’ and Tristan Scaggs’ stories in the final piece.

“We just found over and over again that there was no shortcut for reporting,” Macaraeg said. “I’m proud that we did all of that old school, case-by-case independent reporting.”

Flowers and Macaraeg wanted to be careful when speaking with prisoners and their families about the cases. The people involved in these cases had been accused or convicted of a crime; it just wasn’t murder. They didn’t want to further incriminate anyone through their reporting.

“We wanted to get the whole story, but we realized the dance that had to transpire to make sure we weren’t leaving them in a worse place with their conviction,” Flowers said.

Unsurprisingly, they also found that the prisoners themselves were in shock that they’d been charged with murder.

“There is a healthy amount of disbelief and confusion over how they ended up where they ended up,” Flowers said. “Obviously they understand it now, but it conveyed to us just how crazy the situation is.”

Public reaction

The investigation was the Chicago Reader’s cover story in August, and Flowers said public reaction was “swift and widespread.”

Emails and calls flowed in from people across the country who have been affected by the law. Some readers had children who were incarcerated under its application. Readers responded in shock and disbelief, and other journalists shared it widely.

They also heard from people who are working to change the law.

“It’s been heartening because we weren’t really sure what grassroots activity there was to address this,” Flowers said. “And as a result of the story, we heard from people who are working with legislators in their states and doing what they can to try to tackle this really unfair law.”

Scaggs even called Flowers to thank her for the story. She was in labor when the phone rang.

“And it was Tristan, calling to say thank you,” Flowers said. “I was trying not to bat him off quickly given the situation, but just to hear from him was pretty cool.”

While public reaction has been encouraging, they said systemic changes aren’t likely anytime soon.

“[Change] is slow moving because it connects to very profound, polarizing issues on how we see each other as people and how we organize society,” Macaraeg said. “Staying on this story is something that I’m committed to.”

Contact Riley Beggin at rileyb@ire.org.

Looks like you haven't made a choice yet.