If you fill out the "Forgot Password" form but don't get an email to reset your password within 5-10 minutes, please email logistics@ire.org for assistance.

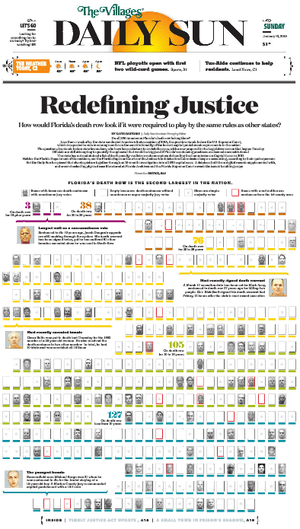

In December 2013, 21-year-old Michael Bargo became the youngest person on Florida’s death row for the brutal murder of a teenage boy. Of the 12-person jury that put him there, only 10 agreed that Bargo deserved to die, and none of them were required to explain why.

In most other states, a unanimous vote is required to sentence people to death. All crimes in Florida, from petty theft to murder, require a unanimous vote to determine guilt.

Sentencing, however, is a different story. Florida has the least stringent capital punishment requirements in the nation: A simple majority vote of 7-5 would have resulted in a recommendation for execution. Even if the jury voted to spare the prisoner from the death penalty, a judge can choose to ignore their recommendation and send the prisoner to death row.

Florida state legislators have for several years introduced bills proposing a unanimous jury requirement; each one has failed. Now, a similar bill is working its way through the state Legislature.

Bargo’s case and the Legislature’s continued resistance to a unanimous jury law intrigued Katie Sartoris, associate managing editor of The Villages Daily Sun. The tiny central Florida paper covers the tri-county area where Bargo committed the murder, and its readers are primarily residents of The Villages, a retirement community.

What Sartoris found over the next 18 months resulted in a multi-story investigation, “Redefining Justice." The project illustrated just how loose Florida’s capital punishment requirements are and explained how the state’s death row would change if unanimous sentences were required.

Building a database

The Florida Supreme Court, Department of Corrections and Justice Administration Commission all told The Daily Sun that they didn’t keep a comprehensive list of death penalty verdicts. So, Sartoris set out to create one herself. She knew that to do that she would need to to find the jury votes for all 390 inmates currently on death row.

“We decided, OK, this is something not only can we do, but we have to do it,” Sartoris said. “No one else has really done this kind of thing.”

She began by searching for digital records on the Florida Supreme Court website. But when the online database contained only recent cases, she and two of her colleagues decided to head to the State Archives of Florida in Tallahassee, over 200 miles north of The Villages. With the help of the Archives staff, they spent four days poring over hundreds of boxes of files in order to find and confirm the jury votes for inmates sentenced since the 1980s.

“We didn’t know what we were doing at first,” Sartoris said. “They told us we’d have to go on to the Supreme Court docket online, find case files, and then give them the case files, which they pooled for us. It depended on how long they were on death row, but these were two or three boxes worth [per inmate], and in each box five or six folders of files. They were huge, huge files. That first day was a little bit of a learning curve, but we got the hang of it eventually.”

Florida’s death row is the second largest in the nation after California, which hasn’t executed an inmate for more than 10 years. The database that The Daily Sun built by searching through records at the Archives revealed that the state’s death row would be 74 percent smaller if unanimous jury votes were required, as they are in 28 of the 31 death-penalty states. If the legislature instead decided to require a supermajority vote (10-2), 43 percent of the state’s condemned inmates would be spared.

Unlike other states, Florida doesn’t require juries to explain why they voted the way they did. Jurors don’t even have to agree on why they want to sentence someone to death. They could choose to vote for execution based on completely different aggravating factors.

They also found that the average time spent on death row has actually increased since the state Legislature passed the Timely Justice Act in 2013. The law requires the governor to sign a condemned inmate’s death warrant within 30 days after his or her final appeals. It also mandates that that the execution take place within 180 days of the warrant’s signing. The clemency process in Florida is confidential, which means inmates and victims’ families have no idea when the inmate will be executed.

Publishing their findings

Publishing their findings

The first installment of the “Redefining Justice” series included Sartoris’ investigative findings as well as pieces on lethal injection drugs, exonerations, and the town of Starke, Florida, the community closest to the prison where the state’s executions take place. Covering the state’s death penalty in such breadth and depth kept Sartoris’ team working up until deadline, but they knew it was a necessary challenge.

“The Florida death penalty in general, it’s like a rabbit hole,” Sartoris said. “Every time we find ourselves finishing up something else, we have more questions. We were right down to the wire for publication.”

When the first segment of Sartoris’ investigation was published on Jan. 10, jury recommendations were just that—recommendations. The judge was the only person with the power to sentence a convict to death. Two days later, the United States Supreme Court decided Florida’s system was unconstitutional, and that juries alone can decide capital sentences.

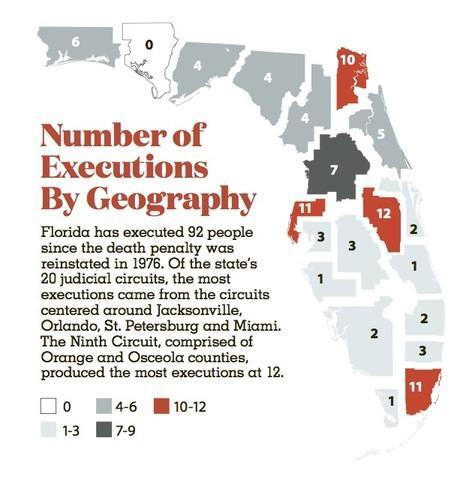

The Supreme Court decision put all of Florida’s death sentences under scrutiny and sparked bills in both state legislative chambers that would alter the sentencing system. Sartoris and her team decided to take a look at how Florida’s past executions would have been impacted by the new decision, and headed back to Tallahassee for another visit to the Archives.

She began to dig into older records in order to see how many inmates had been killed under the newly-unconstitutional judicial override. To her surprise, records from the 1970s did not include any mention of the jury vote. After two days of searching, she found a record on the state bar association’s website of a 1981 Florida Supreme Court case in which the jury recommended the court record the votes. The Supreme Court adopted the policy that year, nearly a decade after the death penalty law was reenacted. But for roughly a decade, there were no records of jury votes on death penalty sentencing.

“We were all pulling our hair out, thinking we had to be missing something,” Sartoris said. “That was probably the toughest thing we dealt with.”

Despite incomplete records on the part of the state, The Daily Sun’s second installment of the series reported that at least five formerly executed inmates would have been spared if Florida’s policy had been found unconstitutional earlier. They also found that two inmates are currently on death row against their jury’s wishes.

More changes ahead

The Florida House of Representatives passed a bill on Feb. 18 that would require a supermajority jury vote for capital sentencing. The bill is currently in committee in the Senate, which used The Daily Sun’s reporting in a workshop for determining how to shape death penalty policies going forward. Another bill, requiring a unanimous vote, will also be up for a vote in the Senate this session.

The state’s lax sentencing standards and long wait times for execution mean that Florida’s sizeable death row costs the state between $8.7 million and $9.6 million every year. That cost — combined with the power of one juror to determine life or death — compelled Sartoris to bring this story to her readers.

“Everyone is a taxpayer here, and everyone has the possibility of being a juror on a capital case,” Sartoris said. “These are the kinds of things you need to know. Everyone has a stake in this.”

Riley Beggin is a graduate student studying investigative reporting the University of Missouri. Follow her on Twitter @rbeggin or send her a message at rileybeggin@gmail.com.

Looks like you haven't made a choice yet.