If you fill out the "Forgot Password" form but don't get an email to reset your password within 5-10 minutes, please email logistics@ire.org for assistance.

It’s like a gold rush. There’s money to be made, but the cost of those riches is a host of harmful, unintended consequences.

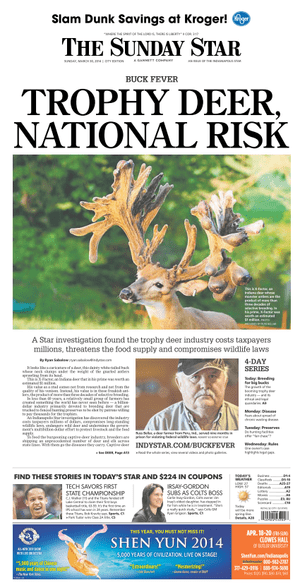

A recent Indianapolis Star investigation uncovered evidence linking lucrative deer farming operations to the spread of invasive lice and diseases such as bovine tuberculosis and chronic wasting disease in wild deer populations. The detailed story, told in five chapters each accompanied by a video, chronicles the rise of commercial deer farming from one Amish farmer with pet deer to the profitable industry that exists today.

“No one really saw this coming,” said Indianapolis Star star reporter Ryan Sabalow.

Sabalow, a long-time hunter, became interested in writing about deer farming after a 2012 press release from the Indiana Department of Natural Resources advised hunters to kill deer with yellow tags in their ears because they could have chronic wasting disease.

Sabalow later learned that the escaped deer that triggered the press release was known as “Yellow 47.” The deer had escaped from an Indiana farm after it was shipped from a site in Pennsylvania that was known to have had deer infected with chronic wasting disease.

Still, Sabalow wasn’t sure of the prevalence of chronic wasting disease, or of the exact nature of its relationship to the deer farming industry. Then he saw the size of the antlers on the deer that farmers were raising across the country. He knew he had something.

The male deer favored by breeders — called “nontypical” bucks due to their large antlers — have impressive racks. In the wild, such deer are rare and highly sought after by hunters.

“We knew there was an interesting business story with possibly with some watchdog elements,” Sabalow said.

So he went to a deer breeder conference in Cincinnati. The event showed him how much money was involved in the industry. (Sabalow went on to feature a particularly famous nontypical buck named “X-Factor” in his story. X-Factor’s estimated worth is about $500,000. His semen sells for $2,500 a unit.)

Sabalow’s next step was to file public records requests in every state asking for documents that would identify the locations of deer farms and high-fence hunting preserves, the number of animals at each facility, and the dates the animals were licensed. He kept track of the requests in a spreadsheet, though many were never filled and some states didn’t respond to his requests at all.

The requests were helpful to the story, Sabalow said, but not in the way he initially expected. While Sabalow got enough data to map the occurrences of disease in wild deer populations, the requests also demonstrated lax federal regulation of the deer farming industry.

One set of records that Sabalow tried particularly hard to get from the USDA dealt with bovine tuberculosis and chronic wasting disease across the country. The USDA told him it didn't have have a database of this information.

“They eventually provided us with disease test results that were a couple years old,” Sabalow said. “You would hope that federal disease trackers would know where diseases happen.”

Case files Sabalow received from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service law enforcement division were so heavily redacted that they became difficult to read.

After spending a lot of time making phone calls and sending emails to follow up on his state records requests, Sabalow eventually decided it would be more worthwhile to get information from other sources.

He ended up relying on a 2007 industry study done by Texas A&M University as well as information from state wildlife agencies. Their findings made a persuasive case that disease in wild populations had originally come from farm-raised deer.

Sabalow also used interviews with those in the industry to get a sense of what was going on.

“It’s interviews that make the story,” he said.

Because he's a hunter and interested in the topic himself, Sabalow said he didn’t have much difficulty getting people to talk to him. Sources understood he wasn’t interested in parachuting in and quickly moving on to the next story, he said.

“We really went out of our way to encourage people to talk to us.”

Avoiding “he said, she said” reporting is key when covering these kinds of issues, he said. As he reported “Buck Fever,” Sabalow continued to circle back to the evidence he'd gathered.

“Eighteen months of reporting allowed us to make declarative statements,” Sabalow said, “The story was fair, but the evidence showed what it showed.”

The online edition of the story was published in five chapters, each accompanied by videos. The chapters helped to give the story narrative flow, Sabalow said, since they released the online version of the story all at once.

“If you only read the print edition, then I think you wouldn’t see the whole story,” Sabalow said. “We spent so much time with these folks.”

Sabalow hopes his story can help start a national discussion about the risks and rewards of deer farming.

“It sure would be nice to have a federal conversation about whether this, as a society, is something that we value, whether the trophy industry is worth it,” Sabalow said.

Follow Indianapolis Star reporter Ryan Sabalow on Twitter @RyanSabalow.

Looks like you haven't made a choice yet.