If you fill out the "Forgot Password" form but don't get an email to reset your password within 5-10 minutes, please email logistics@ire.org for assistance.

Data journalism site Sqoop has added the Department of Justice to its public records database that currently includes the SEC, patent applications and grants, and federal court dockets (PACER). Reporters can use Sqoop to search and set alerts for news tips in these filings.

The new DOJ release includes press releases and speech transcripts from the DOJ's Office of Public Affairs as well as releases from 93 U.S. Attorney's Offices from around the country.

Read more about this release on the Sqoop blog. Journalists can apply for a free account for immediate access to Sqoop's search and rapid alerting platform.

— Bill Hankes, Sqoop Founder & CEO

Editor's Note:

This article first ran on July 20, 2017 on the Investigative Reporting Workshop's website.

By Clairissa Baker and Yang Sun, Investigative Reporting Workshop

A new citywide data policy in Washington, D.C., shows there is no simple way for cities to clearly budget open data initiatives.

Meanwhile, as the city works this summer to implement its newly formed data policy and decide what’s releasable, experts say when more data sets are made available online the result will be better access to information, better journalism and more government transparency.

For investigative journalists, the upcoming data release — expected within nine months after the issuance of the order and adding to the 900 sets already available online — means greater access to information on everything from traffic patterns to invaluable health statistics.

“Just knowing the government has that data is a huge step,” said Kate Rabinowitz, founder of the DataLensDC blog that works to help citizens better understand and access the city’s open data.

But Washington officials can’t seem to determine how much the massive data availability will cost taxpayers. The work being done now at the Office of the Chief Technology Officer is in response to Mayor Muriel Bowser’s April 27 executive order, which calls for an inventory and classification of all government data.

Open data matters differently to each citizen, but it can matter a lot.

One example is Google Maps. Many use this tool every day, and it is based on open transit data from city governments, allowing people to determine best routes and commute times.

Rabinowitz also acts as one of the co-captains of Code for DC, a civic hacker community that translates data sets into content usable to average citizens.

One project Code for DC works on is called Housing Insights. The city has a massive amount of data on affordable housing, “but they are all over the place and it’s kind of messy,” Rabinowitz said.

A team of coders and data scientists collected all the relevant data sets and created interactive visualizations, allowing policy makers and the public to understand what affordable housing looks like in the District and what the challenges and opportunities are.

By sharing civic data, people will become more informed of city services, journalists will tell better stories of the city and institutes will advance their research, said Stephen Larrick, the open cities director for the Sunlight Foundation.

Quantifying the benefits of open data, however, can be as hard as measuring the costs.

“How can you put a price on an informed public,” Larrick said. “And how can you put a price on people having the facts that they are relevant to the decisions that are being made?”

It’s not the first time the city has made data public, but this new policy is an important step in making the government more transparent and accountable, experts say.

A decade after the debut of the city’s online data portal, there are more than 900 data sets available online on a range of subjects from information about 311 calls to crime reports to others on health care and government spending.

As city leaders work to implement the policy, there’s no clear cost associated with the rollout.

“It can be a real irony,” said Larrick. “Many open data programs are about being transparent about things like cost,” yet the cost of the program is obscure.

A number of aspects contribute to the inability to quantify costs of open data.

“Open data is a new thing, and very often it is the thing that is a part of someone’s job, but it’s not someone’s full-time job,” Larrick said.

Employees might work on data infrastructure or web services, among other assignments. Some of these tasks fall into the costs of open data, but unless employees track exactly how many hours they spend working on open data, it is not clear how much.

Not knowing how much open data programs costs is often a barrier to implementing policies.

The city is not at fault for lacking a concrete budget, Larrick said, but “the government should do a better job” of examining and listing these costs.

An analysis of the 2017 budget and the 2018 proposed budget for the Office of the Chief Technology Officer shows multiple line items related to open data, including “data transparency and accountability” and “data governance and analytics.” Even in those line items, however, it’s unclear what is related to the mayor’s new initiative.

Each agency is responsible for finding and categorizing its own data, so the costs are spread out and vary widely depending on the city, a Sunlight Foundation survey found.

One of the biggest differences between cities is whether they use a contractor — two include Socrata and Junar — to host the websites that contain this data.

Washington creates everything in-house; the city pays its staff to create and maintain a website to host the city’s data.

In January 2016, Bowser announced the Open Data Initiative and created the Chief Data Officer position.

About seven months later, Barney Krucoff filled the position, leading a team of more than two dozen people who will reach out to each agency and coordinate data collection.

Before Bowser’s 2017 executive order, technical teams were already in place. After, those were rearranged with staff from Business Intelligence, Geographic Information System and the Citywide Data Warehouse.

“D.C. was the leader of open data in general, but we didn’t have a data policy,” Krucoff said.

He said the District posted its data sets in the early 2000s and built a website hosting data sets published by the government in 2007, both among the earliest in the country. The city even led a hackathon, called Apps for Democracy, in 2008, which Krucoff described as “new and novel of the time.”

US City Open Data Census, research co-conducted by the Sunlight Foundation, Code for America and Open Knowledge International, in 2015 ranked D.C.’s data openness 27th out of 100 cities, as San Francisco, Las Vegas and New York City took the top three positions.

Washington leaders hope to get back to the cutting edge of government transparency with the new data policy. Krucoff said what separates this administrative action from others is that it’s a data policy rather than an open data policy.

The government will not only log and categorize all of the data, but also create a system in which enterprise data is “freely shared among district agencies, with federal and regional governments,” and with the public when the information allows it, according to the data policy.

All city agencies’ data sets will be classified on a scale from zero to four, where level zero data sets have no confidentiality concern and should be completely disclosed to the public.

Significant steps will be taken to ensure the safety of information with privacy and security concerns. The policy includes a host of security protocols for agencies to follow while handling sensitive data sets.

Feedback from the public, such as transparency advocates and civic hackers, helped shape the District’s final version. The drafting team also looked at New York City, San Francisco and the state of Maryland, Krucoff said.

The government will proactively publish a whole class of non-confidential information. This will complement, but not replace, the Freedom of Information Act.

FOIA legally requires government’s reaction on individual requestors and covers items ranging from hard-copy documents to videos.

“I think FOIA will always cover a wider set of material, and open data will cover a more specific set of what we can be proactive,” Krucoff said.

However, there is a gap between the technical language of open data and the accessibility of it by citizens without a computer background.

To bridge the gap, data intermediaries, such as researchers and developers, play an important role. They use the data to make recommendations and tools that the public can understand and use.

Journalists use this resource to find information about their communities. Having information available online makes journalists’ jobs a little easier because the government can place data online that is asked for many times over, instead of responding to requests every day or every month.

“That transparency leads to, I think, a better relationship between government agencies and the public,” said Charles Minshew, data services director at the Investigative Reporters & Editors.

Opening up data is beneficial to both the government and the public, Minshew said, and “it is a true public service.”

Besides the promise of a citywide data inventory, the city also redesigned the online data portal by incorporating more functionality, including visualizations, search functions and interactive tools.

Michael Kalish, Rabinowitz’s counterpart at Code for DC, appreciates the city’s efforts in increasing the website’s usability.

“So I think they’ve very quickly went from something that was not very user friendly to a very approachably useful tool to the community, ” Kalish said.

More needs to be done, however, to make data truly open.

Rabinowitz encounters data inconsistencies and missing records while working with city's open data.

In terms of improving the open data quality, Larrick’s primary suggestion for cities is to reach out to communities and listen to their needs.

“It really makes the benefits of open data a lot more tangible,” Larrick said.

Krucoff hopes going forward that the data policy will empower analysts of each agency to explore the value of data and develop a community in which agencies have a common set of tools and data-minded individuals.

“We generally believe that data is sort of an important asset to the city that we’ve never really known,” Krucoff said.

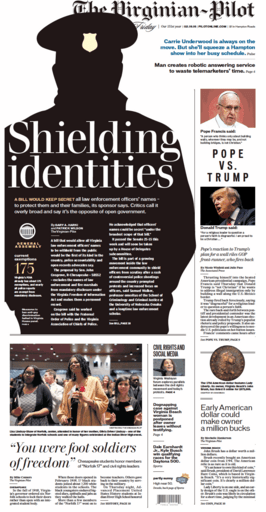

By Gary Harki, The Virginian-Pilot

By Gary Harki, The Virginian-Pilot

In February, the Virginia Senate passed a bill that would allow law enforcement agencies to keep secret the names of all police officers, deputy sheriffs and fire marshals.

It eventually died in a House subcommittee, but only after journalists raised the alarm that the state of Virginia was about to make anonymous the only government employees with life and death power over citizens.

Republican Sen. John Cosgrove, who introduced the bill, said that a Freedom of Information Act request I submitted as a reporter for The Virginian-Pilot was the impetus for his bill. Last summer I requested information from the state’s police training database so that I could track officer movement around the state.

I wanted to look at where officers had previously worked and find out if police that had gotten into serious trouble in the past were able to find work as an officer in a new department. It’s something that I had written about before in West Virginia at The Charleston Gazette.

My interest in this issue started in 2008 following the beating of Twan Reynolds outside of a 7-Eleven by Officer Matthew Leavitt in Montgomery, West Virginia. The officer hit Reynolds over the head with a blackjack, kicked him in the back and sprayed his eyes with pepper spray at close range. Reynolds’s wife, Lauren, and their 4-year-old daughter witnessed much of the assault.

Leavitt singled them out because Twan is black and his wife is white.

Leavitt was on his sixth police department when he assaulted the Reynolds family. While employed in Madison, West Virginia, in July 2006, he had harassed a woman, her boyfriend and her daughter at her home, according to police records. He resigned soon after, and when another department requested a reference, the Madison police chief said he would love to have Leavitt back and that he gets along well with other people.

Leavitt eventually pleaded guilty in federal court and was sentenced to prison on two counts of deprivation of rights under color of law, violations of civil rights law.

Leavitt’s case brought one question to my mind – how often do troubled officers move from department to department without oversight?

Nationwide, there’s little to stop police involved in serious incidents from moving on to another department. It’s a known problem in law enforcement circles, and something The Denver Post is tackling right now.

When I requested a copy of West Virginia’s training database, one manager thanked me for attempting to do the story. The state officials had seen the pattern for years.

I eventually wrote a series of stories detailing my investigation of 13 officers who had left one department following questionable police practices only to find work in another. Several of those officers had moved through the same handful of departments.

After my series appeared, the West Virginia Legislature decided to do something about it.

In 2011, it passed a law that suspends an officer's certification when they leave a police department. If they are hired by a new police department, that department must contact the state and find out why they left their previous department before certification is reinstated.

Virginia’s response to my FOIA request was quite different.

Initially, state officials with the Department of Criminal Justice Services worked to help get me what I need. I requested the first and last names of all officers, the departments the officers worked at, and the hire date and end date for current officers in Virginia.

The journalists in the room, including me, made a different case – that to make police identities secret is to go against one of the basic tenets of our democracy.

DCJS had one concern about handing over the information – they didn’t want the names of undercover officers published. To address this, we agreed to not publish the database in its entirety. To use the information from it publicly, we would have to get a second source for the name of each officer – from previous media accounts or the department itself.

DCJS officials and Virginian-Pilot Editor Steve Gunn signed the agreement.

Days later, state officials refused to hand over the database.

We sued for the information, and in November a judge ruled the department had to hand it over. We got the database in December and by January, Cosgrove filed his bill.

At first it didn’t look like it was going anywhere and would die in the Senate. But once it passed there, Virginian-Pilot statehouse reporter Patrick Wilson and I wrote a story outlining the bill’s ramifications. Other news outlets soon picked up on the story.

It all came down to a House of Representatives subcommittee meeting on Feb. 25. If the bill made it out of committee, it would likely pass the full House and end up on the desk of Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe. Though he’d given no indication about whether he’d sign it, the general consensus was that he would. In Virginia, keeping the public from being able to see the inner workings of government bodies has bipartisan support.

Police union officials and journalists testified before the subcommittee. Union officials said they were concerned about officers’ identities being stolen and that someone could get a list of names of officers in order to do them harm.

The journalists in the room, including me, made a different case – that to make police identities secret is to go against one of the basic tenets of our democracy. We argued that the public has a right to know who its law enforcement officers are and have them be held accountable for their actions.

Legislators voted unanimously against the bill.

I went home relieved and with a copy of the database on my computer.

Now I have a story to do.

Gary Harki is a database reporter for The Virginian-Pilot. You can reach him at gary.harki@pilotonline.com.

By Allison Wrabel

Cole County Circuit Court Judge Jon Beetem ruled that the Missouri Department of Corrections violated the Sunshine Law when it failed to reveal the name of the pharmacy that supplies the drugs for lethal injections.

Under state law, the identities of individual execution team members are to be kept confidential. In 2013, the department added a compounding pharmacy to the team.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri, the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press and reporter Chris McDaniel, formerly of St. Louis Public Radio and now at Buzzfeed, sued the state in May 2014 after they were denied requests for records about the laboratories and pharmacies.

Judge Beetem said the law does not allow the department to "define the execution team as it wishes, without limitation." The law says the execution team is limited to "persons who administer lethal gas or chemicals" and "persons who provide direct support for the administration of lethal gas or chemicals." The court concluded that pharmacies and laboratories are entities, not "persons." In addition, the pharmacies and laboratories are not "administering," or providing "direct support for the administration."

Last week, Judge Beetem ruled in a similar suit filed by former state lawmaker Joan Bray that the department violated the Sunshine Law. A pending third suit filed by other media companies asked a judge to order the Department of Corrections to make public where it purchases drugs for executions and disclose details about the composition and quality of the drugs.

Requesting data or documents from another country can be a confusing and challenging task. What kinds of records are available? Who do you contact about them? Which laws govern their release?

For #FOIAFriday this week we put together a roundup of some of our favorite resources on international records requests. If you have foreign FOIA resources that aren’t included on this list, we’d love to hear about them. Tweet us @IRE_NICAR with #FOIAFriday and we’ll add new ideas to the list.

In ranking the strength of FOI laws, Access Info Europe and the Centre for Law and Democracy place the United States at No. 45 in the world. That’s behind such countries as Uganda, Russia and Kyrgyzstan. Mexico’s law ranks eighth.

David Cuillier of the University of Arizona School of Journalism wrote about what the US could learn from other countries in a 2015 issue of the IRE Journal. We’ve uploaded his column, and you can read it here.

The Data Journalism Handbook has some great tips on general FOIA requesting, but many specifically address access to international records. Some of our favorites include:

Foreign FOI: How to request records in another country (2015)

Emilia Díaz-Struck of Central University of Venezuela offers nine detailed tips for cross-border FOIA requests. These include deciding which language to write your request in, finding the right person to contact and getting help from journalists in other countries.

Global FOI: AP tests laws in 105 countries (2012)

This is an older article, but it still provides instructive lessons on requesting international records. The AP's Martha Mendoza writes about six mistakes she encountered during the AP’s worldwide test of FOI. If your records request involves working with multiple people (or newsrooms), this is a must-read.

100+ tips and tools for news research* (2014)

This tipsheet by Margot Williams contains dozens of links for databases, finding people, accessing different types of information like data, non-profits, corporations and more.

Global Right to Information Rating: Get detailed information on the right-to-access laws of 102 countries courtesy of Access Info Europe and Centre for Law and Democracy. Each country is broken down into 61 different categories, showing what’s open, how to request, timelines to fulfill, etc.

The Global Investigative Journalism Network has a great roundup of resources on freedom of information laws, broken down by country.

Beyond Narco Tunnels: Investigating along the U.S.–Mexico border (2015)

With America’s heightened focus on the U.S.-Mexico border and politicians’ calls to “secure it,” it might be time to ask, how can journalists get better stories about the border, and why should they improve their coverage of it? Celeste González de Bustamante of the Border Journalism Network provides 10 tips.

Investigating along US-Mexico border* (2010)

The AP’s Martha Mendoza offers tips for requesting records from and about Mexico. She lists a few favorite U.S. and Mexican agencies to FOIA when investigating the border and explains what to ask for.

Overview of the Mexican Freedom of Information Act* (2013)

This tip-sheet by Alejandra Xanic von Bertrab discusses the right to information under Mexican law, as well as how to gain access to information for reporting purposes.

Several IRE Conference panels have addressed this issue. IRE members can access the following recordings:

* Denotes resources behind IRE’s member wall

Kansas’ attorney general said Tuesday that emails sent by state employees through private accounts aren’t public record, even when they deal with public business.

Attorney General Derek Schmidt was responding to a question from state Sen. Anthony Hensley about whether such an email would constitute public record. Schmidt, who interpreted "private email" to be an email sent not only through a private account but also on a private device, replied: "In short, we think the answer is 'no.'"

Schmidt had already established in a different opinion that emails in the possession of public agencies are open records, his opinion said. But Schmidt wrote that individual state employees don’t constitute a "public agency" as defined by the Kansas Open Records Act.

Hensley’s inquiry was in response to reporting that showed Kansas Gov. Sam Brownback’s budget director had sent a draft of the state budget via private email weeks before it was publicly revealed.

In response to Schmidt’s decision, Kansas Press Association Executive Director Doug Anstaett released a statement: "This decision essentially says government business can legally take place in the shadows, which I firmly believe most Kansans would reject out of hand," it read in part.

To read more from the Wichita Eagle, click here.

If you report on the government, it may not surprise you to read that only seven of the 21 federal agencies recently FOIAed by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) have provided records more than two months after the requests went out.

TRAC, a research center that administers the FOIA Project out of Syracuse University, has been trying to gather information on FOIA backlogs and processing times. In late January TRAC sent identical records requests to a group of federal agencies – including the CIA, FBI, Bureau of Prisons, several divisions of the Department of Justice and many others.

To avoid running into issues like redaction, TRAC tried to keep the requests as simple as possible: Copies of the electronic files the FOIA offices use to keep track of FOIA requests, include tracking number, date request was received, and the date it was closed. (TRAC posted the full-length letter on its website, and we embedded a copy on the right.)

As of April 24, seven agencies have provided the records:

Four others are making what TRAC considers a "good-faith effort" to comply, but have yet to provide the records. So far, the CIA is the only agency to deny the center’s request.

Learn more about the FOIA Project and see how all 21 agencies responded – or failed to respond to – TRAC’s FOIA request.

Following the April 29th execution of Clayton Lockett, the Tulsa World, along with legal representation from The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, filed a lawsuit against the state of Oklahoma. On Friday, more than 5,000 pages of interview transcripts and other records were released.

The transcripts include about 100 interviews the Department of Public Safety conducted with witnesses during its investigation into Lockett's execution. However, some of the records are heavily redacted without explanation from the DPS.

A hearing in the World's lawsuit is set for March 27 in Oklahoma County District Court.

Read the three-part series from the Tulsa World following the April 29th execution.

By Matt Rumsey, Sunlight Foundation

On Feb. 6, the Office of Management and Budget sent a letter to the Sunlight Foundation explaining how it planned to comply with our FOIA request for Enterprise Data Inventories. These inventories are compiled by 24 federal agencies as part of President Barack Obama’s 2013 open data executive order.

The release, which we believe will represent the largest index of government data in the world, is not just important for open government advocates. It’s important for journalists, researchers and more.

President Obama has made opening government data a priority throughout his term, but has not always been successful in making data easily accessible. The Sunlight Foundation has argued that, for an open data policy to be truly effective, the public must have access to a comprehensive list of government data holdings.

Already, government data sets are regularly used to inform reporting, conduct public oversight, create visualizations, and more. Public access to a proper index of government data will only expand these opportunities.

If the EDIs look how we expect, they should not only list large numbers of government data sets, but also include information that will make this data easier to understand and access. Public data sets will be linked to, and any data that the government chooses to withhold will come with an explanation as to why. In addition, all data will have a human contact point for questions and feedback.

We are particularly interested in seeing these explanations for why government denies access to data sets. Having that information should inform public debate, allow for more targeted FOIA requests, and ultimately result in more data in the hands of journalists, researchers, and other interested parties.

No longer will an interested party have to navigate through the bowels of an agency bureaucracy or send a broad FOIA in the hopes of getting to the data they want. No longer will they look at a piece of government data and have to wonder where to look for more or who to contact if they have questions.

These indexes, if developed and maintained properly by the agencies, will reveal a vast trove of government information to the public. They should empower journalists and researchers to dig ever deeper into the federal government and allow them to uncover stories that were previously uncoverable.

Matt Rumsey is the director of the Advisory Committee on Transparency at the Sunlight Foundation.

A bill designed to improve the way the federal government handles an increasing load of FOIA requests – a bill that had gained bipartisan support – could be dying after a senator blocked the legislation.

The FOIA Improvement Act of 2014 would "create a pathway for the federal government to modernize the administration of FOIA" and "codify the 'presumption of openness' into law," among other changes detailed in a post by Alexander Howard on PBS’ MediaShift.

Retiring Sen. Jay Rockefeller of West Virginia on Thursday placed a hold on the bill. He released a short statement on his decision Friday, saying that the bill might "have the unintended consequence of harming our ability to enforce the many important federal laws that protect American consumers from financial fraud and other abuses."

Rockefeller has until the end of Monday to release the hold, or the FOIA bill dies.

As Howard noted, the bill had already been reworked in order to gain more widespread support and earn passage during Congress' current lame duck session. It had appeared that the changes had worked.

"While it’s still possible that a powerful senator may try to keep this bill from passing, the prospects look good today," Howard wrote two weeks ago.

With Rockefeller’s hold, those prospects turned grim.

If @SenRockefeller doesn’t release his hold today, #FOIA reform won’t pass Congress http://t.co/RwjaWZlMJk Will this be his #opengov legacy?

— Alex Howard (@digiphile) December 8, 2014

Looks like you haven't made a choice yet.