If you fill out the "Forgot Password" form but don't get an email to reset your password within 5-10 minutes, please email logistics@ire.org for assistance.

By Ron Nixon, The Associated Press

In 1895, journalist Ida B. Wells dropped a bombshell investigation into the lynching of African Americans across the nation.

Using data she gathered from accounts in white newspapers — she said no one would believe her otherwise — “The Red Record” showed lynchings were not in response to rape of white women by black men, but often because the relationships were consensual. The lynchings also were used to remove economic competition from blacks, Wells found.

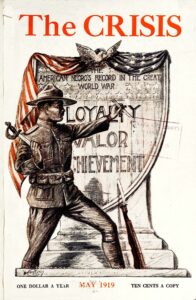

Similarly, during World War I, W.E.B. Du Bois received leaked documents from a source showing the American government had instructed the French to treat blacks the same way they were treated at home.

Later, in 1925, Charlotta Bass revealed in The California Eagle newspaper that the Ku Klux Klan not only infiltrated a local California police department, but also had several black ministers on its payroll.

Although each of these early investigations broke news important to communities of color, none appeared in a mainstream news outlet.

Throughout American history, white-owned media organizations have covered issues of race and discrimination. But when it came to their own hiring practices, they largely reflected society as a whole.

Few, if any, media organizations had people of color on staff in the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s as they tried to cover civil rights struggles and other issues related to race.

That would change in the aftermath of civil unrest in several major cities in the mid-to-late ’60s. Most mainstream media organizations were caught off guard. Few, if any, had reporters with sources or familiarity with the communities of color affected.

President Lyndon B. Johnson meets with members of the National Newspaper Publishers Association in March 1965. Courtesy LBJ Library, Photo by Cecil Stoughton

A panel put together by President Lyndon B. Johnson called the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, commonly known as the Kerner Commission, pointed to widespread racism and discrimination as key factors in the unrest that erupted. It singled out the press with particular criticism. The 1968 report lambasted news organizations for their coverage of race and pointed out the lack of diversity in America’s newsrooms.

“The press has too long basked in a white world looking out of it, if at all, with white men’s eyes and white perspective,” the report found. “Our second and fundamental criticism is that the news media have failed to analyze and report adequately on racial problems in the United States and, as a related matter, to meet the Negro’s legitimate expectations in journalism. By and large, news organizations have failed to communicate to both their black and white audiences a sense of the problems America faces and the sources of potential solutions.”

The report concluded by calling for more inclusion of people of color in newsrooms: “News organizations must employ enough Negroes in positions of significant responsibility to establish an effective link to Negro actions and ideas and to meet legitimate employment expectations. Tokenism — the hiring of one Negro reporter, or even two or three — is no longer enough.”

Over the next few decades, news organizations would begin to hire an increasing number of journalists of color. Yet more than 50 years after the Kerner Commission report’s blistering criticism of media diversity, questions persist about newsroom staffing, said Farai Chideya, a program officer at the Ford Foundation, in a 2018 report about the continuing lack of diversity in newsrooms.

“The Kerner Commission Report was very prescient in the sense that it talked about equity, that people have a legitimate need for representation in the media as being part of a democracy,” Chideya said on WDET ’s “Detroit Today” program. Her report (bit.ly/chideya-report) found that newsrooms have made little progress toward fixing staffing problems, which create blind spots in coverage of race and politics.

Increasing diversity in U.S. newsrooms has been a primary mission of the American Society of News Editors since 1978. But as Chideya’s research found, the effort to bring newsroom diversity numbers in line with national population averages “has not materialized, despite the large demographic shift in America’s racial and ethnic makeup.”

Increasing diversity in U.S. newsrooms has been a primary mission of the American Society of News Editors since 1978. But as Chideya’s research found, the effort to bring newsroom diversity numbers in line with national population averages “has not materialized, despite the large demographic shift in America’s racial and ethnic makeup.”

ASNE’s annual newsroom diversity survey shows Latinos and nonwhites made up nearly 12 percent of newspaper editorial staff in 2000. In 2018, people of color comprised 22.6 percent of employees reported by all types of newsrooms, compared to 16.5 percent in 2017.

Among daily newspapers that responded to the survey, about 22.2 percent of employees were racial minorities (compared to 16.3 percent in 2017), and 25.6 percent of employees at online-only news websites were minorities (compared to 24.3 percent in 2017). Of all newsroom managers, 19 percent were minorities (compared to 13.4 percent in 2017).

People of color represent 22.6 percent of the workforce in U.S. newsrooms that responded to the survey. Yet people of color make up about 40 percent of the population, census data show.

ASNE noted it had historically low participation in the survey, which is now in its 40th year. Just 17 percent (293) of the 1,700 newsrooms submitted information. So, it’s impossible to get a full picture.

There are no comparable surveys for the racial makeup of investigative or project teams at major news outlets. Still, anecdotal evidence suggests they remain overwhelming white and male.

Recent hires or promotions at mainstream and nonprofit news outlets have increased the number of journalists of color in the field of investigative reporting in both management and reporting.

Susan Smith Richardson was hired as CEO of the Center for Public Integrity, and Matt Thompson was tapped as editor in chief of Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting. Both are the

Nikole Hannah-Jones of The New York Times Magazine delivers the 2017 IRE Conference keynote address. Hannah-Jones is a cofounder of the Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Reporting.

first African Americans to lead two of the country’s oldest nonprofit investigative news organizations.

Patricia Wen made history by becoming the first person of color to lead the legendary Spotlight Team at the Boston Globe.

Dean Baquet, who made his reputation as an investigative reporter when he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1988, is executive editor of The New York Times.

Several news organizations now feature young investigative reporters of color as part of their investigative or watchdog teams.

Reporters include Kat Stafford of the Detroit Free Press, whose reporting into city programs has led to investigations by auditors; Faith Abubéy, another young investigative reporter and anchor at NBC-Atlanta (11Alive), has broken several key stories, including investigations about sexual predators on college campuses; and Aura Bogado, a reporter for Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting, has broken several national immigration stories.

Despite these reporters and many others, the overall number of journalists of color in investigative reporting remains abysmally low.

Several journalism organizations are also trying to address the issue, including established organizations such as the Asian American Journalists Association, the National Association of Hispanic Journalists, the Native American Journalists Association and the National Association of Black Journalists, led by President Dorothy Tucker, an investigative reporter for CBS 2 Chicago.

Knight Scholars attend a welcome lunch at the 2015 CAR Conference in Atlanta. The IRE scholarship program allowed college students from several Historically Black Colleges and Universities to attend IRE’s annual conferences and receive mentorship.

IRE, under the leadership of Board President Cheryl W. Thompson of NPR and Executive Director Doug Haddix, also has grown its efforts to diversify the field of investigative reporting. In recent years, IRE has expanded the number of fellowships and scholarships it offers to journalists of color to attend national conferences and weeklong data bootcamps. The organization launched a new yearlong Journalist of Color Investigative Reporting Fellowship and increased the number of journalists of color tapped to speak at conferences and regional workshops.

The Ida B. Wells Society, which I co-founded, was created specifically to address the lack of reporters of color in the field of investigative journalism.

Nikole Hannah-Jones, an investigative reporter for The New York Times Magazine and co-founder of the society, said one of the society’s missions is to “take away the excuse” by giving young journalists of color the tools and mentorship needed to be fully prepared for investigative reporting.

Despite these efforts, the decision to diversify news staffs ultimately rests with those who have hiring power in newsrooms. Diversity must be seen as more than a numbers game. The hiring and promotion of journalists of color are essential for the long-term viability of the American press.

Ron Nixon is the international investigations editor at The Associated Press. He previously served as homeland security correspondent for The New York Times, where he worked for nearly 14 years. He is a former IRE training director and a co-founder of the Ida B. Wells Society.

Check out what else is in IRE’s journal on diversity problems in the journalism industry. This issue is available to members and nonmembers.

Looks like you haven't made a choice yet.