If you fill out the "Forgot Password" form but don't get an email to reset your password within 5-10 minutes, please email logistics@ire.org for assistance.

By Gary Harki, The Virginian-Pilot

By Gary Harki, The Virginian-Pilot

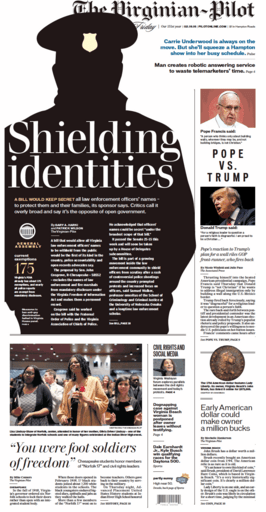

In February, the Virginia Senate passed a bill that would allow law enforcement agencies to keep secret the names of all police officers, deputy sheriffs and fire marshals.

It eventually died in a House subcommittee, but only after journalists raised the alarm that the state of Virginia was about to make anonymous the only government employees with life and death power over citizens.

Republican Sen. John Cosgrove, who introduced the bill, said that a Freedom of Information Act request I submitted as a reporter for The Virginian-Pilot was the impetus for his bill. Last summer I requested information from the state’s police training database so that I could track officer movement around the state.

I wanted to look at where officers had previously worked and find out if police that had gotten into serious trouble in the past were able to find work as an officer in a new department. It’s something that I had written about before in West Virginia at The Charleston Gazette.

My interest in this issue started in 2008 following the beating of Twan Reynolds outside of a 7-Eleven by Officer Matthew Leavitt in Montgomery, West Virginia. The officer hit Reynolds over the head with a blackjack, kicked him in the back and sprayed his eyes with pepper spray at close range. Reynolds’s wife, Lauren, and their 4-year-old daughter witnessed much of the assault.

Leavitt singled them out because Twan is black and his wife is white.

Leavitt was on his sixth police department when he assaulted the Reynolds family. While employed in Madison, West Virginia, in July 2006, he had harassed a woman, her boyfriend and her daughter at her home, according to police records. He resigned soon after, and when another department requested a reference, the Madison police chief said he would love to have Leavitt back and that he gets along well with other people.

Leavitt eventually pleaded guilty in federal court and was sentenced to prison on two counts of deprivation of rights under color of law, violations of civil rights law.

Leavitt’s case brought one question to my mind – how often do troubled officers move from department to department without oversight?

Nationwide, there’s little to stop police involved in serious incidents from moving on to another department. It’s a known problem in law enforcement circles, and something The Denver Post is tackling right now.

When I requested a copy of West Virginia’s training database, one manager thanked me for attempting to do the story. The state officials had seen the pattern for years.

I eventually wrote a series of stories detailing my investigation of 13 officers who had left one department following questionable police practices only to find work in another. Several of those officers had moved through the same handful of departments.

After my series appeared, the West Virginia Legislature decided to do something about it.

In 2011, it passed a law that suspends an officer's certification when they leave a police department. If they are hired by a new police department, that department must contact the state and find out why they left their previous department before certification is reinstated.

Virginia’s response to my FOIA request was quite different.

Initially, state officials with the Department of Criminal Justice Services worked to help get me what I need. I requested the first and last names of all officers, the departments the officers worked at, and the hire date and end date for current officers in Virginia.

The journalists in the room, including me, made a different case – that to make police identities secret is to go against one of the basic tenets of our democracy.

DCJS had one concern about handing over the information – they didn’t want the names of undercover officers published. To address this, we agreed to not publish the database in its entirety. To use the information from it publicly, we would have to get a second source for the name of each officer – from previous media accounts or the department itself.

DCJS officials and Virginian-Pilot Editor Steve Gunn signed the agreement.

Days later, state officials refused to hand over the database.

We sued for the information, and in November a judge ruled the department had to hand it over. We got the database in December and by January, Cosgrove filed his bill.

At first it didn’t look like it was going anywhere and would die in the Senate. But once it passed there, Virginian-Pilot statehouse reporter Patrick Wilson and I wrote a story outlining the bill’s ramifications. Other news outlets soon picked up on the story.

It all came down to a House of Representatives subcommittee meeting on Feb. 25. If the bill made it out of committee, it would likely pass the full House and end up on the desk of Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe. Though he’d given no indication about whether he’d sign it, the general consensus was that he would. In Virginia, keeping the public from being able to see the inner workings of government bodies has bipartisan support.

Police union officials and journalists testified before the subcommittee. Union officials said they were concerned about officers’ identities being stolen and that someone could get a list of names of officers in order to do them harm.

The journalists in the room, including me, made a different case – that to make police identities secret is to go against one of the basic tenets of our democracy. We argued that the public has a right to know who its law enforcement officers are and have them be held accountable for their actions.

Legislators voted unanimously against the bill.

I went home relieved and with a copy of the database on my computer.

Now I have a story to do.

Gary Harki is a database reporter for The Virginian-Pilot. You can reach him at gary.harki@pilotonline.com.

Looks like you haven't made a choice yet.